Effective Altruism vs. Buddhism: same goal, different approach

Changing external factors vs. changing internal factors

Effective Altruism and Buddhism have very similar goals. Effective altruism, in general, wants to minimize suffering (and maximize happiness) of all sentient beings. Buddhism, perhaps even more ambitiously, aims to end all suffering of all sentient beings in existence.

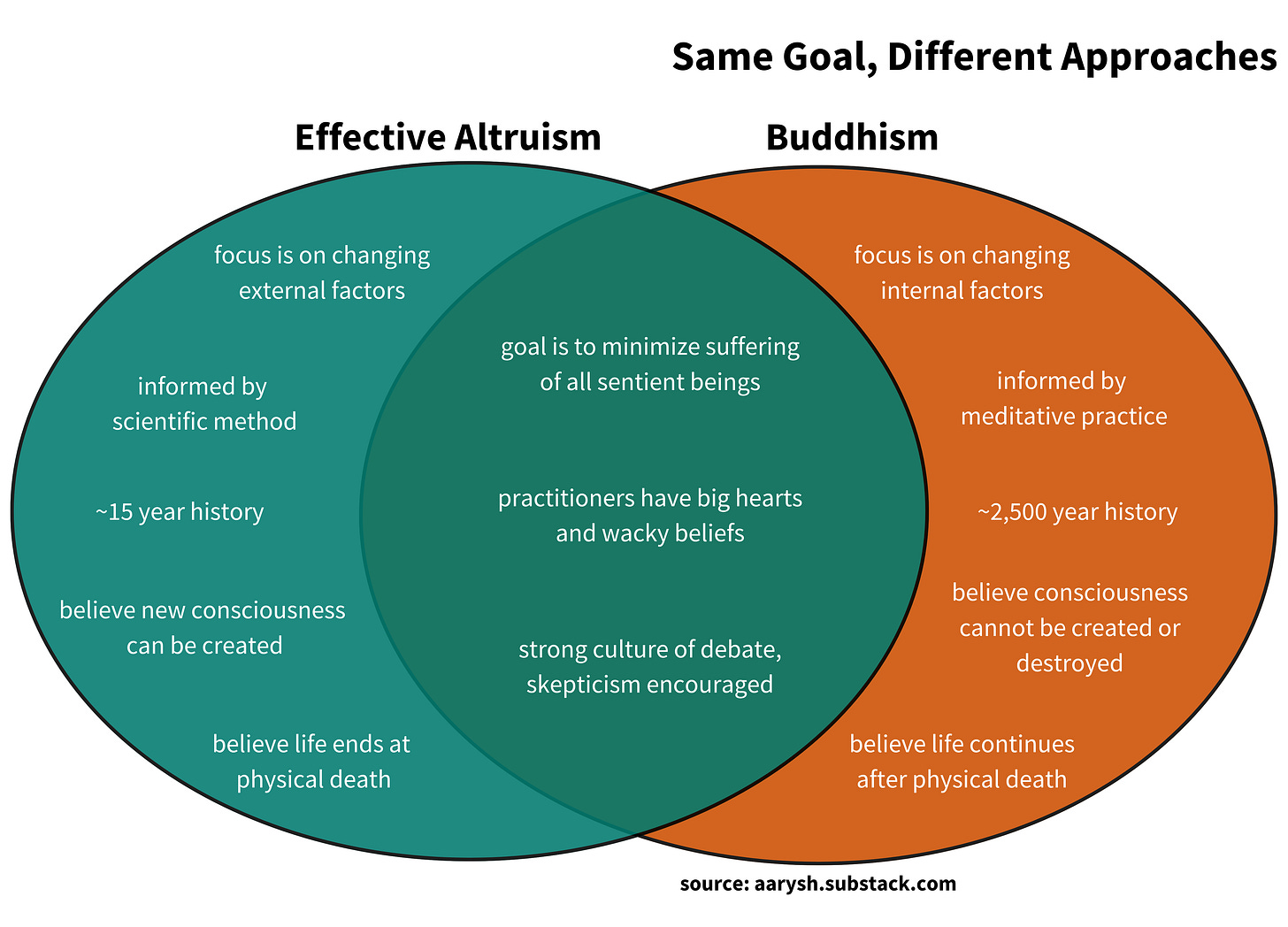

Both movements encourage students to be skeptical, investigate, ask questions, and verify things for themselves. It’s interesting, then, that the two arrive at different approaches. Those differences are due to differences in underlying assumption, and are summarized by the venn diagram:

Background on Buddhism

Buddhism was founded 2500 years ago by Siddhartha Gautama, the most recent Buddha in a long line of Buddhas. Many of Buddhism’s assumptions were likely inherited from the region in India in which it was born—however, Buddhism didn’t take all of the local region’s assumptions as default true. For example, Buddhist literature spends quite a bit of time refuting both annihilationism (the belief that consciousness ends at death) and eternalism (the belief that an unchanging, eternal soul hops from body to body). Buddhist discussions are usually framed within and are responses to existing eastern philosophy.

Buddhist philosophers believe that our consciousness-stream doesn’t end at death but is only transformed, that the habit energy developed in this life will influence the conditions of the next life, and that permanent escape from suffering can only be reached through enlightenment.

The path towards enlightenment is one of self-transformation. And simply starting on the path (without necessarily aiming for full enlightenment) improves a person’s life—and the lives of everyone that person encounters.

Self-transformational activities include the cultivation of loving-kindness, compassion, concentration, equanimity, inner-peace, and mindfulness through meditation. The path also includes more basic things like not harming others, not lying, not gossiping (with the intention to divide).

To understand the benefits of self-transformation, you can compare two people—one who has developed mindfulness, equanimity, and inner-peace and one who has not. Put them into the same situation—standing in line at the DMV, not getting an expected bonus at work, or losing a home to an earthquake. In those situations, both individuals may suffer, but the person who has not developed inner-peace will suffer more, and furthermore, will lash out at others and create even more suffering.

Thus, following the path of self-transformation will reduce suffering in this life, in the next life, and cultivates the necessary habit energy to attain enlightenment in a future life—and, if enlightenment is reached, then that means one less sentient being in the universe is experiencing suffering.

Background on Effective Altruism

Effective altruism was born in a time of materialism, of immense scientific progress, of capitalism and extreme global inequality, and of a decline in traditional religious belief systems. The generation that raised effective altruists had retreated from religion—which was seen as both internally inconsistent and inconsistent with scientific discoveries. So, their children (who would go on to become effective altruists) were raised in nihilism, existentialism, and lacked a straightforward moral code to follow.

So, emerged their own moral system called effective altruism, that they would build up to be internally consistent, and be written in a language that they could understand.

The movement began as a little non-profit called “Giving What We Can”, which encouraged people to pledge 10% of their lifetime income to charities. Fifteen years later, there are now multiple effective altruism foundations that raise money, do research into methods of “doing the most good”, and evaluate charities based on effectiveness. One common way to evaluate charities is by the number of expected lives saved per dollar given. Today, effective altruist foundations raise hundreds of millions of dollars a year, and the movement itself counts billionaires among its members and has the ears of governments through lobbying efforts.

For a while, the idea of “Earning to Give” was popular. The idea was to go into a high-earning career—like finance or tech—and give most of your income away to charity. Sam Bankman Fried, a prominent effective altruist, followed this path. He raised billions of dollars for a cryptocurrency startup called FTX with the promise to give most of his wealth away. However, FTX went bankrupt, he lost his investors’ money, and he was sent to prison for fraud. Because of that incident, “Earning to Give” is no longer popular, but effective altruist groups still prioritize approaching already wealthy people to convince them to donate towards their causes.

Effective altruism has been accused of being cult-like again and again and again and again, both by people sympathetic to and critical of the movement. For one reason, some branches seem to semi-worship (or at least play with the idea of) a not-yet-existing artificial superintelligence in the future that may retroactively judge us for our actions today. For another reason, the San Francisco branch has a sub-culture of polyamory, and this is a characteristic reminiscent of cults.

That aside, since the days of “Giving What We Can” the effective altruist movement has developed three main branches:

Those that want to help the (currently alive) global poor

Those that want to help the (currently alive) animals

Those that want to help the (not yet born) people, animals, and/or sentient AIs of the distant future.

The discourse around that last branch, known as longtermism, is most controversial.

Overall, effective altruisms focus is clearly on changing the external factors of the world, rather than the internal factors that may help us storm the unavoidable rocky seas of life.

Comparing the Two and Personal Thoughts

In my mind, they have the same goal, the people drawn to either of these movements have love and compassion in their hearts for all living beings. I see no reason why someone can’t incorporate aspects of both. However, I am personally extremely critical of EA. Partially, because I can easily see my younger self getting sucked into the vortex that is EA, and also because I now consider many of their teachings misguided.

(For example, the main EA effort to evaluate charities based on quantitative metrics reminds me of the failures the same approach had in evaluating (and incentivizing) schools based on test scores and researchers based on number of publications. I wrote about it before here. I also think that EA borrows too much from the authority of science. Ethical models, unlike scientific models, cannot be empirically tested. Why: because there is no ground truth answer of “what you actually, really should do” to test the model against. If you’re clever, I’m pretty sure you can make an ethical model such that whatever answer you want pops out. I can still see value in developing these models, but EA needs to be more upfront about the limitations of ethical models as compared to scientific models.)

Comparing EA with Buddhism also demonstrates that the underlying assumptions of EA can be challenged and aren’t default true. If we set up all of the right external conditions would that minimize suffering? Or is there something, difficult to measure, that effective altruists are missing?

If we gave a person all of the external conditions that they think they need to be happy, will that person be happy? Buddhism says, not for long. Reducing suffering requires changing internal factors, too.

Or, let’s say that an effective altruist has done a bunch of calculations and figured out the correct course of action to take (the right charity or the right career). Would that individual be able to maintain focus and not be seduced by wealth and power? Buddhism has practices to help develop focus and navigate those temptations.

I know I’ve been extremely critical of EA so far, and I do have criticisms of Buddhism as well—however, those are much smaller in comparison. This is probably due to the fact that Buddhism has had a much longer time to develop and to refine its arguments and stances. The many criticisms that Effective Altruism has faced in the last few years, I think, are more than justified, and this young movement should continue to be placed under scrutiny. Hopefully, effective altruism continues to respond and adapt to criticism, and, hopefully, they end up doing more good than harm.

It’ll also be interesting to see, what the next generation—the ones raised by effective altruist parents—will do…since it is only human nature for teenagers to reject the follies of their parents.

I didn't know there was an actual official movement based around altruism, but the roots, starting from moving away from religion while wading through philosophies like nihilism, mirrors my own recent reconversion and moral/ethical rebuilding.

You made a good point about EA not having a consistent objective standard to measure good acts against. I can't remember if you made this point, but it seems EA and Buddhism can function as opposite faces of the same coin; EA geared toward extrinsic good and Buddhism toward intrinsic good. (I can't think of a better word than "good").

Thank you for sharing this breakdown and exploration of these two concepts!